Tuesday, August 30, 2005

Did you get that ugly skirt?

Mom and I never agreed on clothes. In most other ways I was basically, "Momma's little miniature." But when it came to clothes or decorating the house, we disagreed on everything. She was all dusty rose and country blue. I was all brown and forest green and burgandy.

So on my first Christmas in Senegal, I opened up my package from Mom. One of the presents in it was this gorgeous rayon broomstick skirt, which was all the rage among American expats in Dakar who were trying to stay covered to their ankles so as not to offend the locals, yet keep from melting in the intense tropical sun. The skirt was long and black with a few deep red flowers on the bottom hem and a drawstring with a tiny bell on the end. I loved it.

Then I called Mom at the appointed hour and the call went just like this, the same as every week:

"Hi, Mom. It's me. Call me back."

"Hi, Punkin Head. How are you? Did you get your package?"

"Yes, I did. Now call me back."

"Okay. I miss you so much. I wish you were here."

"Me, too, Mom. I've just spent $18 on this call please call me BACK!"

"Oh, right. Okay, okay."

-----------------------------

"Did you get that ugly skirt?"

"Yes, I did and I LOVE it!"

"I knew you would. I just picked the ugliest one I could find."

I got it free

She didn't just love this card. She was being facetious. If it had birds or flowers or butterflies on it, she pretty much hated it. So I was surprised to find it in my mailbox one day. Once I read it, I cracked up.

And that little drawing under "Mom" has a story of its own. One day when I was in high school I got home and she pushed a piece of paper across the table to me. A corner of it was covered with these little drawings. One or two, her favorites, were circled.

"Guess what it is?"

So we played a never-ending game of twenty-questions until she finally said, "Okay, I'll just tell you. It's half a tuna salad sandwich with lettuce and a frilly toothpick."

It didn't mean anything. It's just what she'd had for lunch. But it struck her funny and she decided that this was going to be her symbol. My best friend and I signed our notes : ) and = ) and Mom wanted to have something, too. So hers became that--a half a tuna salad sandwich with lettuce and a frilly toothpick.

It's one of the few samples of her handwriting I have. It's kind of like hearing her voice.

Tuesday, August 23, 2005

Karin Leak

My parents and my brother called me Karin Leak ever since I can remember. Several reasons float around in my mind as to why--it's a variation on my middle name, Lee; something about leaky diapers as a baby. Who knows really. But my favorite story comes from my brother.

He's seven years older than me and to him I was sort of like a little doll or toy brought home to entertain him. He called me Karin Leak like my parents did, but he also sometimes called me Drip. The two monikers were related, you see, leak...drip. But it was likely an indication of his summation of my intelligence.

So one day when I was 4 and he was 11, I asked him why he called me Drip and Karin Leak, he told me this story with great flowery gestures.

One day we were taking a walk and there appeared in the sky a huge water faucet.

We were so amazed. Then a drop of water began to form, growing larger and larger, and it fell to the earth. And it was you. A big drip.

Monday, August 22, 2005

Sleeping with the Enemy: I am the Enemy

I used to think that all my good traits came from Mom and all my bad traits came from Dad. I was compassionate and patient, smart, witty and funny like my mother. I was a short-tempered, critical, tactless, over-sensitive control freak like my father. It was a very convenient way to deify and vilify them in turn. That worked for me for a very long time.

Then I got married.

One thing most people don't tell you in your pre-marital mad rush to plan the perfect wedding that pleases everyone is that actually being married is like being in a 360 mirror--there's no way to avoid your short comings. Suddenly you realize that you have idiosyncracies, which go unnocticed when you live alone. When you live alone you think you're perfect. Okay, when I lived alone, I thought I was perfect.

Everything was where I wanted it to be and it stayed there until I moved it. I had a whole set of dishes, glasses and silverware, but I only ever used one of anything and just kept washing it, putting it in the rack to dry where it'd be waiting for me when I needed it again. Who needs cupboards? A fork, a knife and a spoon, a bowl, a plate, a glass and a skillet are all you really need. This was a life I loved so much that I was looking for happiness outside my perfect little apartment by myself.

So when I found the future Mr. Karin Stanley, I didn't quite realize that he'd actually have to live with me. That's been the hard part. Sharing sinks that I think should be dry to be considered clean and toothpaste tubes that I think should never have toothpaste on the outside of them. And towel racks that are hung level so that the towels will actually hang straight rather than at odd angles.

I could go on. I mean I could really really go on and on, but then I realize how lucky I am because--no wait, I mean what is it with putting away the groceries. He's like, "I don't know where this goes." And I say, "Here's an idea--how about next to the other things that are just like it." Sometimes I'll get really pedantic and say, "Hey look, I'm putting the beans with the beans and the tomatoes with the--tomatoes. It's a revolutionary system I like to call organization." This is never appreciated the way I think it will be.

I have to give him this though, it takes a lot of courage to put away groceries in the house of a control freak, because he knows as soon as he's done and leaves the room, I'm going to go back in there and rearrange everything and bitch and moan about it the whole time. Oh, who am I kidding, I'll see he's doing it wrong and elbow my way in there before he screws it up even further. I suppose it would be one thing if I thought it was good enough to put beans with beans, tomatoes with tomatoes, but no. I've got to complain about red beans with red beans, black beans with black beans, diced tomatoes with diced tomatoes, stewed with stewed. All the while making sure all the labels are facing front like that creepy scary husband in Sleeping with the Enemy.

But, honestly, it makes so much sense to me. It's so obvious that this is the way it should be. I get so frustrated with all these stupid little things, and they are never ending, that I even heard myself think, "I love him, but I just can't live with him." And then I knew. I knew I had just turned into my father, who had said nearly word for word the same thing about my mother.

Within the first year or two of our marriage, which could easily be classified as the worst, I discovered that my mother told my brother that I had married someone just like my dad, which was not a compliment but an exasperated sigh of incredulity. I can see her point a bit, my husband and my father were both made constantly wrong throughout their childhoods and daily ill-parented and therefore carried around with them this huge, crippling fear of making mistakes that didn't manifest itself as perfectionism, as in some, but as paralyzing self-doubt and an inability make friends or be easily liked. Okay, I can see that.

But what they didn't see, of course couldn't see, was how completely in love with me my husband was, and still is. How well he treats me, how he tells me every day that he loves me, and that I'm beautiful no matter how much I scoff at the idea, and how much he respects me and

all women, clearly unlike my father. And that on the really big issues--money, kids, politics, religion and wall color, we agree.

all women, clearly unlike my father. And that on the really big issues--money, kids, politics, religion and wall color, we agree.As it turns out, I prefer to sit on the couch and watch TV all night, waiting for my husband to walk by on his way to anywhere so I can ask him to get me a glass of water or turn on the fan or shut the blinds because I'm too damn lazy to get up and do it myself. I'd ask him to pee for me if I thought it would work. "Hey, while you're in there, pee for me, too, would ya. I don't wanna miss this Trading Spaces reveal."

Yup, I am my mother's daughter. And my father's. Like it or not.

Sunday, August 21, 2005

I love your hair!

A poem by Alison Luterman that I wish I'd written:

I stalked her

in the grocery store: her crown

of snowy braids held in place by a

great silver clip,

her erect bearing radiating tenderness,

the way she placed yogurt and avocadoes

in her basket,

beaming peace like the North Star.

I wanted to ask "what aisle did you

find your serenity in, do you know

how to be married for fifty years,

or how to live alone,

excuse me for interrupting, but

you seem to possess

some knowledge that makes the

earth burn and turn on its axis" -

but we don't request such things

from strangers

nowadays. So I said

"I love your hair!"

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

When I lived in my mom's house, in my mom's town, just after she died, I used to see this woman at what would have been my mom's Fred Meyer, had she lived long enough to have seen it open and long enough to have seen Roth's close, where she had shopped every week since we moved here in 1982 and where she and one other woman in town bought L&M cigarettes, which is the only reason Roth's still carried them. So this woman at Fred Meyer, who I saw every Sunday evening when I did my shopping, looked exactly like my mother with her long grey hair pinned up with a clip, with her broad sloping shoulders, big butt and labored walk, made difficult by the probably 200 extra pounds she carried on her bones.

I asked my mother once--when I was little and she was probably only about a 100 pounds overweight, but it seemed like more because of the way Dad called her a fat, lazy slob all the time--"Mom? Are fat people really, really strong because they hafta carry around all that fat? Or...?" She said that no, fat people were not strong, they were tired.

So here was this woman who looked just like my mom that I saw every Sunday night at Fred Meyer. And every week I'd forget and be shocked to see my mom shopping. I wanted my mom to be alive so much that I imagined that she hadn't really died, but had just needed a break from her life and so had faked her death and was really living in Arizona somewhere, but came up to Canby, Oregon to buy groceries late on Sunday nights and somehow didn't think that I'd see her. I'd walk up to this woman every week to tell her that it was okay, that it was hard, unbelievably hard to lose her, but that it was okay if she just needed a break and that I was not mad, that she could come back. But then she'd turn toward me just enough and I'd see that this wasn't my mother after all and I'd have to pretend I'd mistaken her for someone else or was looking beyond her at a sale sign or something.

For a couple of years, actually, and even now sometimes, I fantasize that she's really not dead but living in Arizona somewhere, taking a break. But then I remember her cold body on her bedroom floor, which I insisted was cold from the air conditioner, and how I cried to Todd, "She's not here. Whatever made her her isn't here anymore." And that I have a box of ashes in the basement that used to be her pink, fat, warm body that meant Mom to me and I realize that there's no way around it. My mom is dead and she's not coming back and I hate that.

Mom used to read aloud to me

Mom used to read aloud to me, as a good mom should.

When I was little, of course I loved it--the sound of her voice, the warmth of her body, the sweet time together. As a teenager, trying to individuate, trying to find out who I was separate from my mother, I began to hate her reading voice. But we still read a lot to each other, a lot more than other parents and adult children. We read stories from the newspaper to each other, stories from the Reader’s Digest. Occasionally I read my lines to her or from my own writing. She would always be astonished and say, “You wrote that? You thought that up right out of your own head? I don’t know how you do it.”

Sitting at the dining room table, Norman Rockwell pictures hung crookedly on nicotine stained mauve wallpaper. The door to the garage, which never shut quite right because it didn’t hang square, would slam shut, jarring the wall and making the mini pitchers fall off their tiny country shelf under the Norman Rockwell pictures. A dirty lace table runner on a heavy wood table that would look better in another kind of house. Dusty plastic flowers in a clear glass vase anchored by glass pebbles. A full crystal ashtray. My feet up on the plank of wood that ran under the length of the table. “You still like to have your feet up? You used to always put your feet up when you were a kid, one foot on my leg, the other on your father’s.”

I don’t know why I didn’t like her voice when she read. She sounded too sweet, too June Cleaver. I’m not sure.

What I wouldn’t give to hear her voice right now.

I have stories, too.

It just occurred to me that I have stories, now, too. I used to love to listen to my mother tell stories about the people at her work. The residents and her co-workers alike—and they weren’t always easy to tell apart. Her co-workers were sometimes just as crazy as the residents with alzheimer’s and schizophrenia. She loved them all. She loved us all. And as we sat around the kitchen table after dinner doing the Word Power and the Jumble, she’d tell me stories about her people.

I always ran off at the mouth about my day and my dramas and she loved to listen. But now—just now—I’ve realized that I have people, too. Students and co-workers and stories to go with them. But she’s not here to tell them to. So I’ll have to write them down before I die and take them with me.

Like the way Alex and I pretend to flirt in front of his wife of 35 years who is never listening, which is perhaps a natural consequence of 35 years of marriage to a flirt. And how easily I confuse tall, thick-waisted Cuban men in their 40s like Dario and Lazaro. And Osmani, the chrystal-eyed mime and actor who could tell right away that I am a performer, too. And Tatiana & Valeriy K with their smooth kind faces, broad smiles and four beautiful daughters. And Andrei, also with dazzling blue eyes that used to be so thrilled as he awaited fatherhood, now vacant and sad since the miscarriage after the first trimester.

And Daysy who wept wordlessly at my desk during a break. I consoled her the way a woman consoles a woman—a touch on her arm, small murmurs from my throat and an open face that says, “It’s okay to cry. You just go ahead.” For 15 minutes we connected just as women, like friends, dropping the pretense of teacher-student, American-Cuban. Just women. And Vasyl, with three short fingers on one hand. He told me how it happened once and I hate it that I forgot. Something about fixing a machine in Siberia. And Nereyda who is 24, the same age as I was when I lived in Senegal. She’s so tall and chestnutty brown with gorgeous almond eyes. She has an enormous butt, which I hope every day is bigger than mine, that she somehow squeezes into stretchy pants—usually white. It looks less like she’s wearing pants and more like she’s been dipped into white chocolate.

And Nelea who blushes almost constantly, who I thought was 21, but is really 30. I was disappointed in myself when I realized that I treated her with more respect after I learned her age. Imagine—me—doling out agism despite perpetually feeling I’m at the receiving end of it. Since infancy I’ve been furious that no one would listen to me or ask me what my pre-verbal self thought! Of all the nerve!!!

These are my people. These are my stories. And I’m gonna tell them.

11/21/04

Bridge to Heaven

I read Broken Music, Sting's memoir of his childhood until the Police. I highly recommend it, but have a dictionary handy; he's got quite a vocabulary.

When he was in his mid-30s both his parents died of cancer a few months apart. He said he didn't really deal with it for a long time, just kept himself busy. So I was reading through the song sheet from his "Soul Cages" CD which came out in '91, about five years after his parents died, and found lots of tiny references to them and his loss of them including this one:

If a prayer today is spoken

Please offer it for me

When the bridge to heaven is broken

And you're lost on the wild wild sea

Lost on the wild wild sea...

And for the first time in the fourteen years I've been listening to that song, I finally understand that part. It's unfortunate that I finally get it, but I'm grateful for even a single line that puts it into words for me.

Our parents are our "bridge to heaven", that buffer between the life we think we know now and the life that comes next, which is always a mystery. But how much do we really know now? We think we know what's coming, but we have no idea really.

You can be chatting with co-workers at a completely micro-managed job when someone coaxes you into the restroom to tell you your mother has died. Then, instead of complaining about managers and slow computers, the room starts spinning and the floor drops out and you're on the phone with your brother who , like you, can only say in the saddest worst voice ever, "Oh NO. Oh, God, no!" And suddenly you begin to understand those pictures of old babushkas wailing over rumpled bodies that used to house their children.

You can be driving back from a weekend of meditation, feeling centered, peaceful and calm and that you really felt the prescence of God that evening at 5:30. But then you walk into the house and find your husband in the silent living room with that look, a look you've never seen on him before, but nevertheless you know.

"Who died?" you ask. "Someone died, didn't they?" He says, "Yes, someone died. I don't know who. You need to call your brother." So you call your brother and brace yourself. His wife answers and tells you to call your brother's cell phone right away. She won't say more. So it's not one of the kids, or she wouldn't be able to speak. It's likely to be one of your grandparents, they're in good health, but old. But if it had been them, she would have told you, probably.

It's Dad. It's probably Dad. And it was. You call your brother who's driving back from the hospital where Dad's body had been taken, but not allowed to be seen--just as well. You're still calm from your weekend and ask, "How are you doing?" Your brother says with a sigh, "Well, you know. We just did this," referring to when your mother died three years earlier. You begin to wonder if your calmness is a result of all the meditation you've been doing this year or the relief you're not surprised you feel. And should you feel bad about that?

And a few days later at your brother's house in NY you learn that your father died right before you felt that strong connection to God. You don't know what that means, but it feels like a sign. A sign of what? That you're being cared for in some way? Maybe, except that now that you truly are an orphan at the age of 33, you feel completely untethered, definitely at risk of floating off into space to slowly die of heat or cold or starvation or suffocation and certainly isolation. And maybe no one will notice.

When the bridge to heaven is broken

And you're lost on the wild wild sea

Lost on the wild wild sea...

And then he doesn't even finish his sentence...he's just lost on a wild wild sea.

That makes sense to me now.

Sugar Sugar

My mom often called me Sugar.

"Hey, Sug, come here and help me with this."

"I sure do you love you, Sugar."

But here's how it really went.

She said, "When you're really good, I call you Sugar Sugar. When you're just good, I call you Sugar. And when you're bad, I call you Sugar Shit."

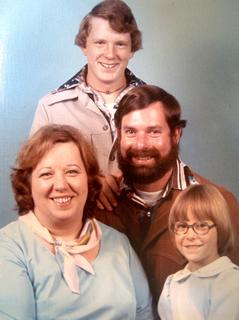

As in, "Ooh, you little Sugar Shit," said through clenched teeth after I'd done something to annoy her. Like take this picture of her napping.

Late 1970's in NY.